Critical Opinion: Oliviero Toscani, or Why Fashion Needs a Visual Punch

Oliviero Toscani passed away.

And with him, perhaps, a certain idea of boldness.

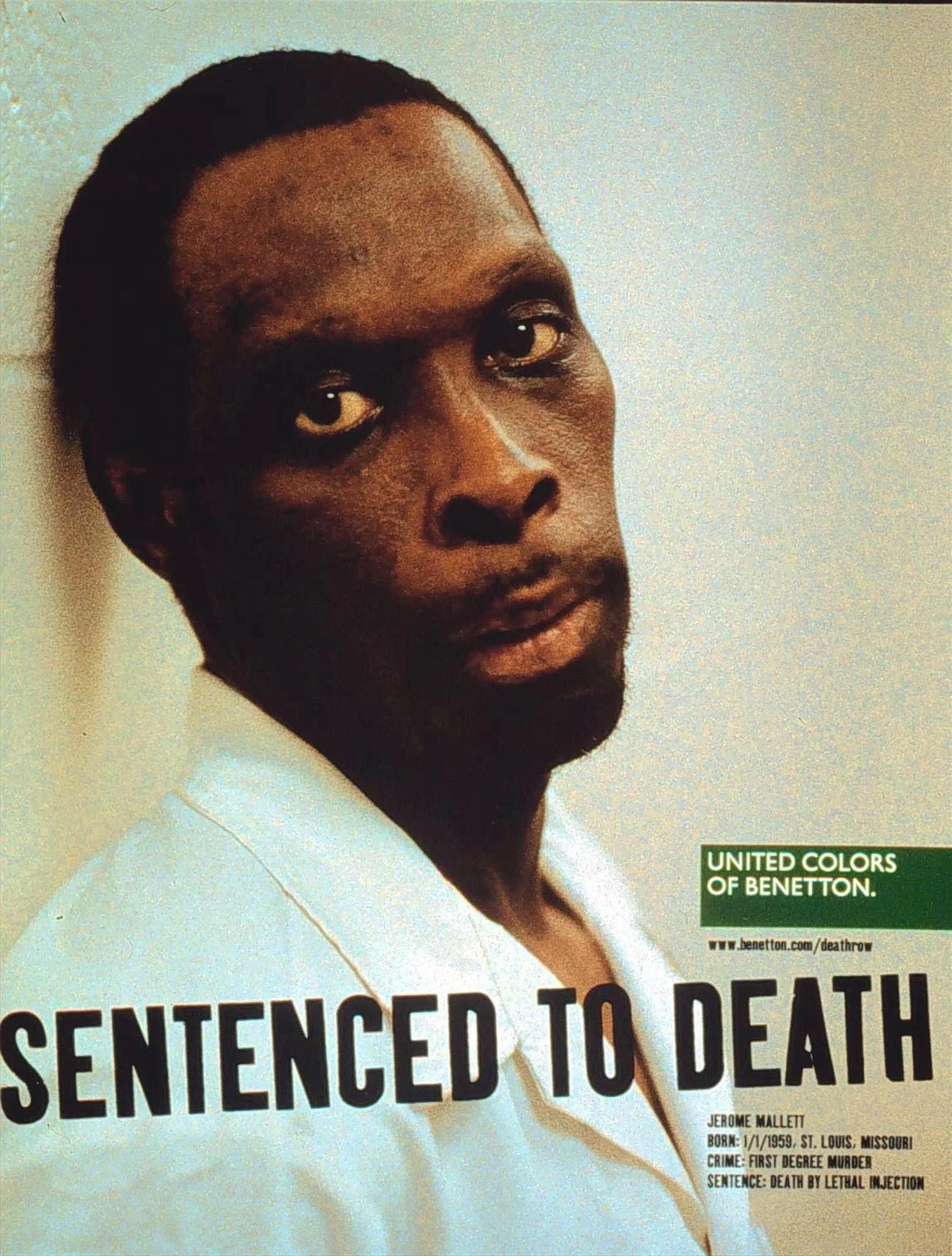

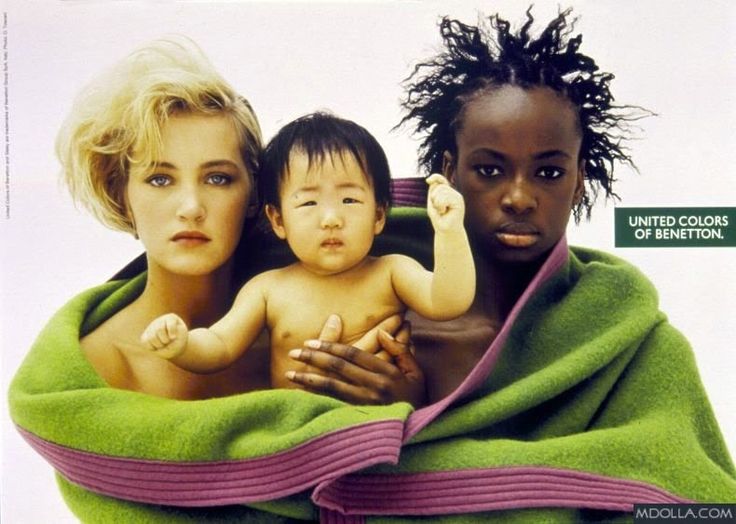

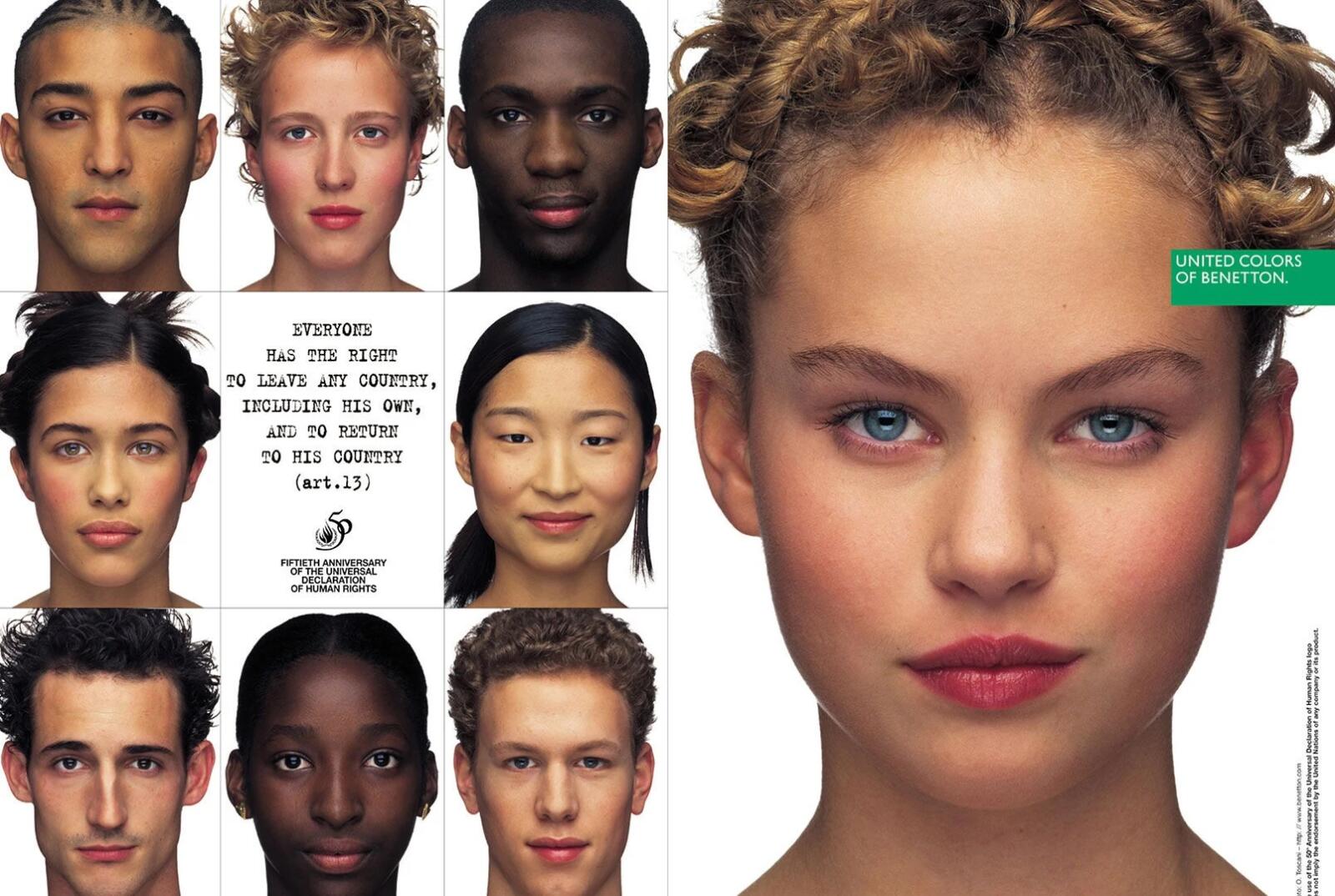

The Italian photographer, known for his campaigns with Benetton, proved that advertising could be much more than a call to consume.

A newborn baby still covered in blood,

an AIDS patient on their deathbed, death row inmates:

Toscani never tiptoed around the truths people preferred to ignore.

He didn’t gift Benetton with avant-garde, untouchable images£

– he offered something rarer:

a political reflection, a visual cry that transcended clothing.

Benetton. Not Prada, not Comme des Garçons.

An accessible, everyday brand. That was Toscani’s genius: injecting a burning discourse into the mundane. His vision was clear: fashion, even the most ordinary ready-to-wear, has the power – and responsibility – to inspire cultural change.

This wasn’t hollow activism or meaningless slogans slapped onto a logo; it was a direct, visual, unforgettable stance.

And perhaps that’s his greatest lesson: an ad that doesn’t spark controversy, that doesn’t unsettle, is useless.

The word controversy has been watered down, reduced to cheap provocation.

But Toscani reminds us of its true meaning: taking a stance, igniting debate. A controversial ad is one that speaks. Not to the consumer, but to the human being. It awakens, shocks, confronts. Without that, it’s just background noise, an empty distraction.

Toscani understood that to move people, you have to force them to think, to leave them with the uncomfortable aftertaste of a question unanswered.

Where has that audacity gone today?

Our time campaigns are filled with carefully calibrated diversity and sanitized eco-marketing, but where are the campaigns that provoke, that disrupt?

The industry would rather stroke consumers’ wallets than make waves.

And yet, in a world grappling with climate, social, and political crises, the need for impactful visual discourse has never been greater.

Toscani understood this: fashion isn’t just an industry of image – it’s an industry of symbols. Every campaign is an opportunity to question, to influence, to reinvent.

Why do luxury brands, supposedly at the forefront of avant-garde, leave the heavy lifting of political discourse to $30 activist T-shirts?

Where are the images that shock, that stick, that give fashion the narrative power to transform culture?

What Toscani leaves us with is a lesson: beauty alone is not enough. It must unsettle, provoke, inspire. Fashion has a role to play in shaping the future, but it must have the courage to face its time.