ARTE POVERA is having a Parisian Moment: 5 Artworks to be the Light of the Party

Arte Povera, the 1960s Italian movement that rebelled against the elite art world, is once again in the spotlight in Paris.

Currently featured at two of the city’s most prestigious venues — the Bourse de Commerce and Galleria Continua — this movement, born out of Italy’s social and political upheaval, is being reexamined.

But what keeps us so intrigued by Arte Povera today? Could it be the revival of humble materials in a world obsessed with excess? Is it the art world’s answer to “quiet luxury”?

In an era where art has become another luxury item, Arte Povera offers a raw, almost soothing antidote with its modest materiality.

Here are five works that perfectly capture the spirit of this movement, reminding us that simplicity, even in art, can be a quiet act of rebellion.

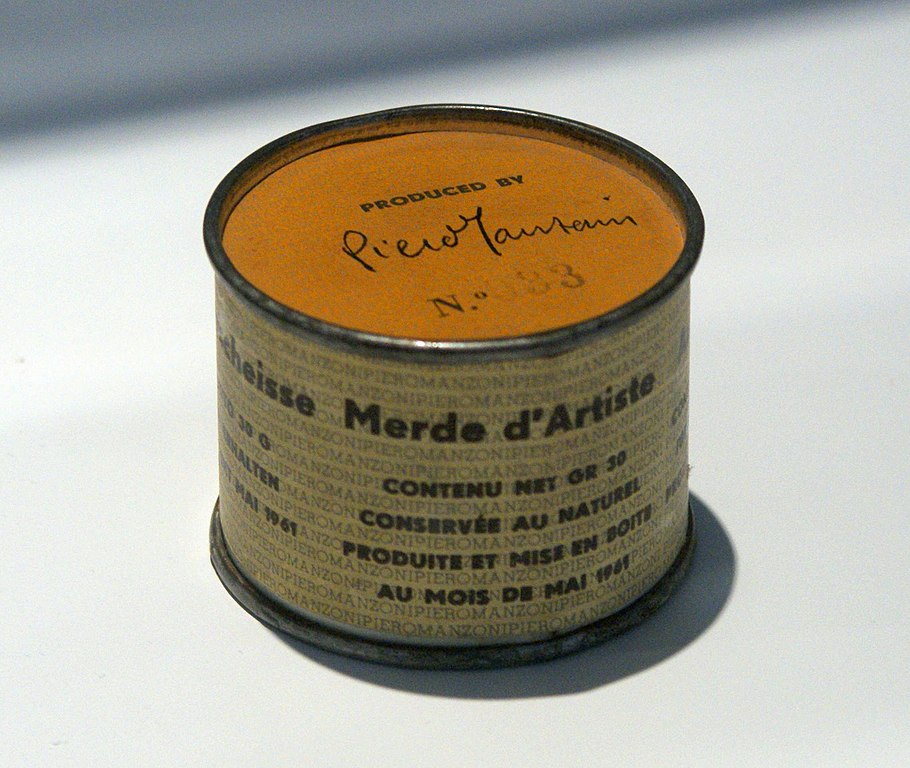

Piero Manzoni – Merda d’Artista (1961)

Piero Manzoni, a born provocateur, created Merda d’Artista as the art world was redefining itself in an age of consumerism. As art became more commodified, Manzoni flipped the script. His tins of artist’s excrement were a sharp critique of art as a commodity, mocking collectors willing to buy anything from a “big name” artist.

At a time when Pop Art was turning art into mass production, Manzoni laid bare the fetishization of the artist. The fact that these tins now sell for hundreds of thousands of euros only adds to the irony: Is the artist’s authenticity valuable, or are we just consuming art like any other product?

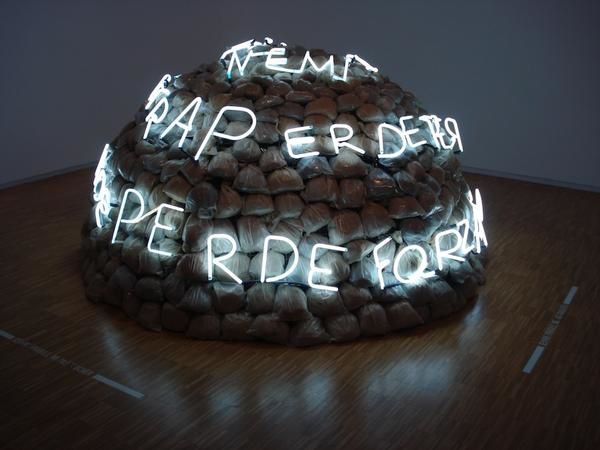

Mario Merz – Igloo di Giap (1968)

Mario Merz is one of Arte Povera’s most iconic figures, and his Igloo di Giap is both politically and philosophically charged. Created during Italy’s student and worker revolts in 1968, this igloo represents a primal need for shelter and survival. But Merz takes it further by incorporating modern materials like glass and metal, subtly critiquing industrial society.

The work’s name, Igloo di Giap, references General Võ Nguyên Giáp, who famously led the Vietnamese to victory at Diên Biên Phu. Merz imbues his work with revolutionary energy, evoking resistance against dominant forces. This isn’t just a shelter; it’s survival in a world where even simplicity is a luxury made industrial.

The question here is:What are we sheltering from? The natural elements, or the cold pressures of modern society?

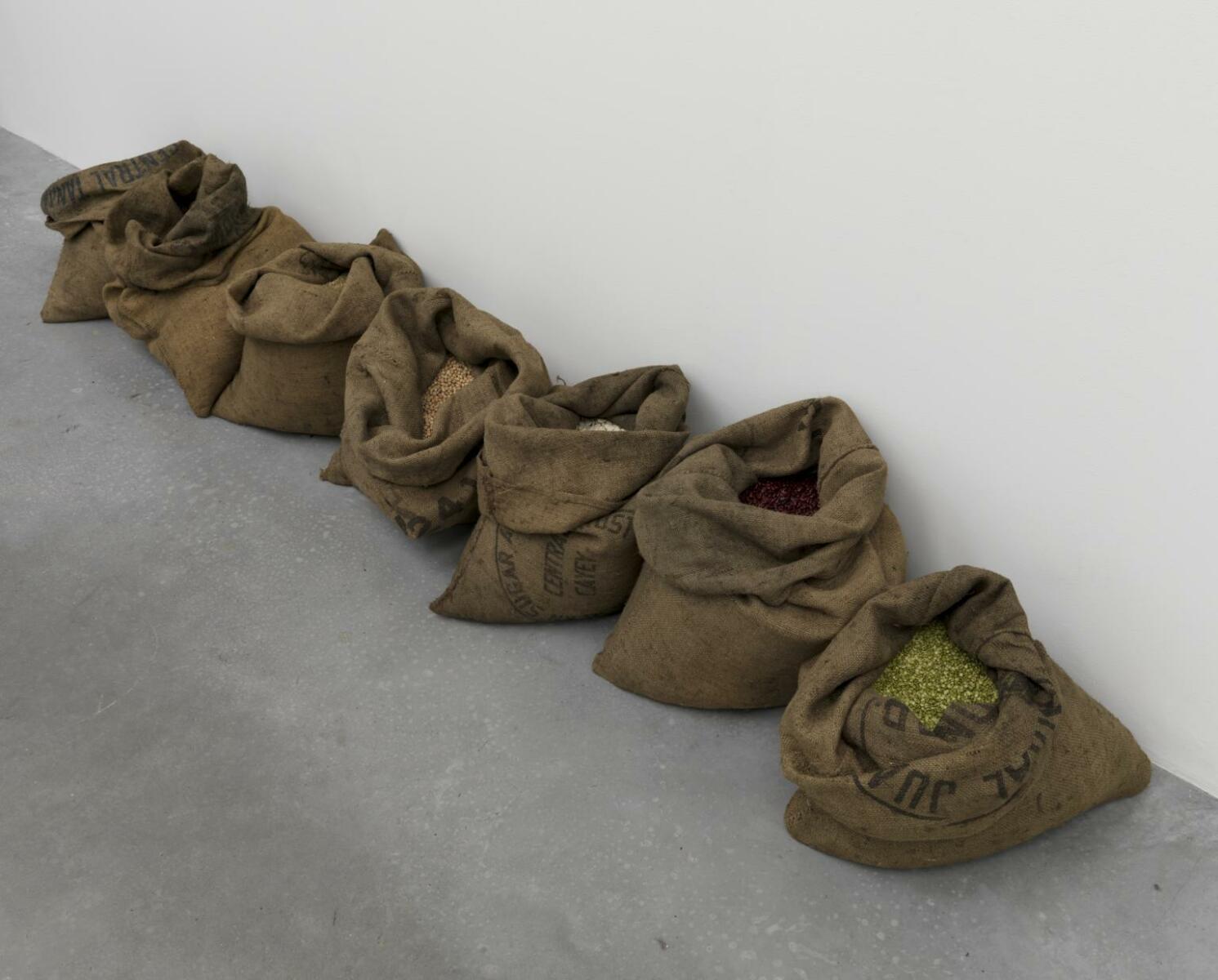

Jannis Kounellis – Untitled (1969)

Jannis Kounellis’s work, featuring sacks of grains and legumes, embodies the Arte Povera philosophy perfectly. Created for the exhibitionLive in Your Head: When Attitudes Become Form, the work was a last-minute solution when Kounellis’s original piece got stuck at customs. He quickly sourced basic foodstuffs from local markets, transforming them into art.

This piece speaks to the global political unrest of the late 1960s — student protests, rising leftist movements, and economic concerns. The materials reflect survival, poverty, and global exchange. It’s a metaphor for life’s cycles, resource fragility, and international trade.

Kounellis asks us:Do we see food, or the very weight of existence?

Giovanni Anselmo – Untitled (1968)

Giovanni Anselmo’s work confronts nature and industry head-on. A lettuce balanced atop an industrial stone block, held in place by a thin wire. The contrast between the ephemeral (the lettuce, destined to rot) and the permanent (the stone) symbolizes the tension between natural forces and industrial modernity.

At a time when Italy was rapidly industrializing, Anselmo’s piece reflects the conflict between man and nature, sustainability and fragility. What might seem ordinary becomes a powerful metaphor for the looming environmental crisis.

His question is clear: Nature or industry — who will outlast the other?In the age of climate change, this resonates louder than ever.

Michelangelo Pistoletto – Venus of the Rags (1967)

Pistoletto’s Venus of the Rags makes a bold statement about consumer society. In the late 1960s, Italy, like much of the Western world, experienced rapid economic growth but also social inequality. The juxtaposition of a classical Venus and a pile of discarded clothes symbolizes the clash between what is timeless and what is disposable.

This work is a biting critique of consumerism, where both products and people are used up and thrown away. Pistoletto captures the decline of traditional values in the face of a throwaway culture, questioning the role of beauty in a world drowning in waste.

As Yves Saint Laurent famously said, “Fashion fades, style is eternal.”

Beyond the passing trends, some things are meant to last, even amid the chaos of modernity.